DIGITIZING COUNTY RECORDS:

TROUP COUNTY COURT AND GOVERNMENT RECORDS

NHPRC FINAL REPORT

NAR07-RD-10013-07

January 1, 2007 – May 31, 2009

1. Objectives:

a) flattening and scanning 53 linear feet of Troup County court records

b) Converting the Guide to Troup County Records to EAD and using automated scripts to create folder level records

c) Linking the scanned images to the folder level EAD records

d) Creating microfilm of the scanned images for long-term preservation

e) Testing the usability of the digitized materials with at least two focus groups and reporting on the results of the tests

f) Developing tracking methods to explore use of the digitized collection and compiling annual reports for at least three years after completion of the project

g) Developing a website that publicizes the project and describes the processes used at both the Troup County Archives and the Digital Library of Georgia

h) Publicize the project and its methods through press releases, announcements on appropriate listserves, articles in at least two publications, and presentation of the project during at least one professional conference.

2. Summary of Project Activities

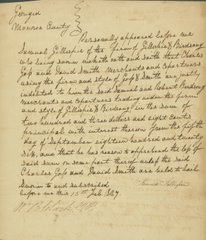

The Troup County Scanning Project has been successfully completed. The full 53 linear feet of Troup County court records were flattened, scanned, and posted on the Digital Library of Georgia website. 76 years of court records have been scanned meeting our goal of scanning all the 19th century court records for the county, which date from 1825 to 1900. Scanning was performed in accordance with guidelines prepared by staff of the Digital Library of Georgia. Converting the 1986 finding aid for the Troup County court records into a Microsoft Word file and then to an EAD file was a critical component of the project.

The Troup County Archives kept five part-time staff members busy scanning for much of the grant period. The Troup County Archives staff has worked with the Digital Library staff to name and number image files to match the finding aids. Additionally staff at both institutions worked to link files with the database. Finally, a blog created to chronicle progress of the project was updated periodically.

3. Accomplishments

a) Flattening and Scanning

Eleven people volunteered at the Troup County Archives (TCA) to assist in flattening the documents and prepare them for scanning. A total of 600 volunteer and staff hours were spent completing the project. Flattening was completed during the spring of 2007.

In mid-May, 2007, staff began scanning the flattened documents. During the first period of the grant, three linear feet were scanned. By January 2008, an additional 10.5 linear feet of materials have been scanned. By July 2008, 29.5 linear feet have been scanned out of a total of 53 linear feet. As of December 31, 2008, 39 linear feet have been scanned. Finally, by May 31, 2009, all 53 linear feet originally recommended for the project were scanned. Due to the fragile and unique nature of the 19th century court records, scanning preceded slowly, though the pace picked up considerably after the first few months. Two members of our scanning staff averaged 25 to 30 hours per week. We tried to have three additional people to work on the scanning project when the regular staff members are off duty. During the last year of the project, scanning was done 95% of the time during the hours we are open. (This is one of those areas where small institutions may struggle more than larger places that have more staff and more student assistants to call upon.) Eventually, we came up with a system to have scanners going almost full time.

Despite the juggling of staff members and working hours, plus the need to ask for an extension for the project, we were delighted that the full span of years, 1825-1900, was completed during the grant period. We can tell scholars and other users of the materials that all the 19th century loose court records have been scanned and made available on the DLG website.

b) EAD Conversion

A consultant who works with the Digital Library of Georgia as her full-time job (Sheila McAllister) completed EAD conversion of the 1986 finding aid. Ms. McAlister authored a Perl script to generate the folder-level DC metadata records. She also directed Archives staff on how to name the individual scans and documents – a critical component in making sure files and inventory listings matched up. (Note: this part of the project was billed to the grant during the January 2009 – May 2009 cycle.)

McAllister reports:

The finding aids for the project are available at http://dlg.galileo.usg.edu/troup/

Dublin Core records for these may be searched at: http://dlg.galileo.usg.edu/CollectionsA-Z/court_search.html.

c) Linking scanned images to EAD

At the end of the grant period in May, 2009, the Troup County Archives had delivered approximately 3029 gigabytes or 136,428 images to the Digital Library of Georgia for processing. TCA and DLG staff performed quality reviews of the documents. DLG staff then generated test derivative files (pdf/djvu), and made adjustments to the workflow to more thoroughly automate the cropping and de-skew process. The goal was to automatically link scanned images with the finding aid. During the early and middle months of the grant, DLG staff also checked the scanned images and the file names used. A few images had to be rescanned. By late 2008, the majority of the quality control work began to be done by Troup County Archives staff. Folder naming and numbering, deskewing and cropping were the major items carefully examined during quality control phases.

d) Creating microfilm

We originally intended that this be done during the grant period but due to time constraints, we decided this would be done after the scanning was completed. We have been in consultation with staff at the Georgia Department of Archives about having microfilm created from the scanned images. The Troup County Archives always planned to pay for the creation of microfilm from local funds and will do this.

One note: should staff at Georgia Archives or Troup County Archives decide that it is not economically feasible or practical to create microfilm from the scanned images, we do believe we have enough redundancy built into the system to keep the scans available to the public. Copies of actual files are in digital storage at DLG and TCA. Should microfilm not be created, then we expect to file a 3rd digital copy at State Archives.

DLG staff and TCA staff are committed to making sure that forward migration of files is done at the appropriate time. The files are currently high quality tiff files, an industry standard. At some point in the future, should it appear that tiff files are no longer accepted formats; the files will be converted to other acceptable file types.

e) & f) testing the usability of the digitized materials and developing tracking methods These two aspects of the grant will be explored in more depth in coming months. The Digital Library of Georgia has added measures to look at page viewing and time spent on these parts of their collection. We will be looking at use statistics as the months pass. As for testing the usability of these digitized 19th century court records, this was done at the Troup County Archives using genealogists and local historians. Everyone was very happy with the layout of the DLG site and with the basic finding aid structure. Many times, the actual scanned image is easier to read than the original document. The scanned image can more easily be enlarged and contrast levels adjusted than the original can be. Such adjustments make reading the scanned document easier than reading the original. The real test will be as historians and genealogists not connected with DLG or with TCA begin to use the collection in their research. The main questions will be whether the collection enables them to find needed materials and in a timely fashion.

g) Developing a website that publicizes the project and describes the processes used at both the Troup County Archives and the Digital Library of Georgia has been in place for most of the grant project. A blog was created and has several articles on it, including an article describing the flattening process and also the EAD conversion process. The blog can be seen at http://troupscanning.blogspot.com/. This blog will be updated with final results in the next few weeks. During the project, we realized maintaining the blog takes committed effort. If the future, if we decide to do a blog or a similar website, different people will be assigned responsibility for adding to the blog in different weeks and different months in an effort to keep the blog fresh and lively.

h) Publicize the project

The LaGrange Daily News has included several articles about the grant, including one top of the fold, at the beginning of the project. Additionally, the Troup County Historical Society newsletter has included several articles. The project has been mentioned in the newsletter of the Association of County Managers and in an article in the Atlanta Journal Constitution about the IMLS “Preserving America” conference. An article in Annotations about the project was released in Spring 2009. In future months, efforts will be made to have additional articles about the availability of the actual files on the DLG website in the LaGrange, Atlanta, Columbus, and West Point, GA., newspapers plus in newsletters and journals of professional publications, including Provenance and American Archivist.

Project Director Kaye Minchew was a speaker in a panel discussion about digitizing collections in the 2008 Annual meeting of the Society of American Archivists in San Francisco. She prepared a one-page article for Outlook, the newsletter of the Society of American Archivists for their September-October issue. We are also seeking to have an article in Provenance, the Journal of the Society of Georgia Archivists and in American Archivist. Finally, Minchew was on a panel at the 2009 annual meeting of the National Association of Government Archivists and Records Managers talking about scanning projects. At the 2008 SAA meeting, the Troup County Archives received the “Council’s Award for Exemplary Service.” This tremendous honor helps draw attention to the award.

4. Assessment

The original goals of this project generally appear to have been overly optimistic regarding the time involved though the goals of the project were met with a time extension. Now that the report is completed, we are more convinced than ever about this scanning project being a model for other scanning projects. We firmly believe that creating minimal metadata and spending minimal time processing the collection is an excellent way to do archival scanning projects.

At TCA, we are trying to follow this example in processing projects at the Troup County Archives with both manuscript collections and government records. Specifically, we are currently doing a major updating and revising of the Troup County Archives’ website (www.trouparchives.org). With the new website, we plan to include for the first time lists of government records and be ready to insert scanned pages as they become available. For instance, in June, 2009, we began scanning pages of Troup Inferior Court minutes. The Inferior Court heard both misdemeanor cases and acted as county commissioners in the early decades of Troup County’s existence. On the website, we will post scans of the pages and include very brief descriptions about the minute books. We expect to do similar processing of manuscript collections and hope to include scanned images of some of our most popular collections.

SPECIFICS: Things always take much longer than expected. I doubled the expected time for scanning documents when writing our grant proposal but still underestimated the time the project would require.

Staff can often cause delays. We started out by hiring two people to do the scanning. One of these people worked for about three weeks before finding out her mother was terminally ill. She worked a few hours a week for awhile before quitting. Another staff member who worked 25 to 30 hours per week during much of the grant had an adult son die during the project as a result of complications from diabetes and kidney dialysis. He was in the hospital several times for about four months. She worked some and usually when she was not at work, another staff member could be put on her scanning station. These life events cause delays but cannot be avoided. We hired another person who worked extremely slowly and she quit about the time she was picking up speed. At the end of the project, we had two very capable people plus two students who fill in on their off days who are doing excellent work. We were also fortunate to be able to hire a young man with asperger syndrome at about mid-project. He has been one of the best scanners we have ever hired. He worked very conscientiously, took few breaks, and was very careful.

The project should have started at full force. Due to Federal budgeting issues, we were not sure when the project was going to start. We started with Phase I, unfolding and flattening of documents. We should have started Phase II, scanning, about 3 days later after Phase I commenced, just as soon as the first box of documents had been flattened. Instead, once we learned we could begin the grant, we started phase I and ordered our first Epson scanner. It took about several weeks to get the scanner from Epson. (This was not an in-stock item at the local office store.) Then the scanner had been bumped in shipping and had to be shipped back taking at least another three weeks. This all cause fairly significant delays. In retrospect, I wish we had gone ahead and ordered the scanner when we learned we would get the grant as soon as funding was approved but we are a very small shop with limited funding and this was not possible.

Making estimates of time is tricky, especially if you do not have the exact equipment you are going to use in the project. In estimating the amount of time each scan would take when we were writing the grant, we had to use a Minolta scanner for our example. The per-scan time was different than the Epson (DLG recommended the Epson). Also, we did not realize when preparing the grant that we needed to use Professional scans rather than home scans. This added a couple of minutes to every scan. We seriously underestimated the scanning time.

To speed up scanning, we would need to scan at 100 dpi but the lower dpi would not produce the quality of scans that DLG or the Troup County Archives would like to produce. We have consulted with Toby Graham, head of the Digital Library about increasing the speed of the project and are in agreement that the quality of the product is the most important part of this project.

Finally, a more positive lesson: this NHPRC grant has greatly strengthen the possibility of Troup County Archives undertaking future scanning projects. We have two excellent large-format scanners and we understand the processes needed to implement the projects. We believe even more strongly than ever that scanning is an excellent way to increase access and also to preserve documents. Original documents can be handled twice (flattening and scanning) and then viewed many times without further damaging the documents. Scanning provides an exciting opportunity to deliver documents in the future. Creating minimal metadata also greatly improves the ability of TCA and other institutions to undertake such scanning projects.

5. Costs

As flattening the documents took 400 hours at $9.00 = $3600 (these hours were donated by volunteers) plus 200 hours by TCA staff at $19 per hour = $3800. A total of 600 hours and an equivalent of $7400 went into flattening and document preparation. (Staff time was spent supervising volunteers, reboxing, reshelving, preparing new shelf list, labeling boxes, etc.) Average cost per linear foot to flatten and prep $139 per linear foot. (Note: $9.00 per hour was chosen because some of the volunteers had extensive professional experience in working with technology while others had no experience.)

Converting paper copy of finding aid to word file 50 hours at $33.00 per hour = $1650 (volunteer hours donated by the Project Director, work done on her own time.)

For staff members performing the actual scanning of documents, the basic cost has averaged $8.50 per hour. Additional costs include the scanner hardware and software plus overhead and computer storage. In the first reporting period, 232 hours were spent scanning about 3 linear feet. Salary costs were $1906. In August, 2007, we projected that it would take 3850 hours to finish the project.

As of January 2008, 1162 total hours have been spent on scanning for this project. As of July 2008, a total of 2528 hours have been spent on scanning. By the end of December 2008, 4229 hours have been spent on scanning or reviewing the files. By May 31, 2009, the grant ended with a total of 6824 hours being spent on scanning and reviewing files. Scanning 19th century documents is slow and time-consuming. Individual pages of a file are often different sizes and pages are sometimes attached with glue or a wax seal that cannot be removed. Care has to be taken to not damage the documents.

Our goal since August 2007 has been to spend up the process and get more scanning done more quickly. We have consulted with Toby Graham of the Digital Library of Georgia but have agreed that the only way to really speed up the process is to change our scanning specifications – to perhaps 100 dpi rather than 300 dpi and scan as a personal or home project rather than in professional mode. We all agreed that we are unwilling to lessen our quality standards. We need 300 dpi scans done in professional mode scanning and saved as high quality tiff images for publishing on the Internet and for preserving into the future.

Through May 31, 2009, we have scanned 136,428 files in 4900 folder and 3000 gigabytes.

Expenses include equipment, salaries for scanning staff plus TCA & DLG staff, volunteers, equipment, supplies, travel, and conversion to word for the finding aid. Billed expenses are $155,729. We divided this amount by the total documents scanned. Our cost to date for scanning 19th century court records is $.87 per page. The only way I can think of to get this cost down further is to do a much larger collection OR not have to purchase equipment and software. Certainly the 87 cents per page is the final cost per page for the Troup County grant but the number can be further. Given the fragile nature of the 19th century documents and the paper they are on, I do not think the process for this grant could be done differently or that we could have gotten the cost per page down much more.

6. Impact

The impact of the project on the grant-receiving institutions, especially on the Troup County Historical Society, has been significant. Staff at the Archives continues to reconsider processing methods of larger collections and may begin scanning more collections, especially if we can minimize the time-consuming creation of metadata.

Project co-director Toby Graham reports:

“The Troup County Superior Court Records digitization effort has provided the Digital Library of Georgia with a potentially far-reaching opportunity to explore digitization of archival records and historical manuscripts on a scale that significantly surpasses our previous efforts. Prior to the Troup project, the DLG’s normal process for converting handwritten historical records was to transcribe by hand, encode the transcripts in TEI/XML, describe the materials at the item-level, and develop a system for full-text searching and textual display. While this approach yields many benefits in terms of usability, it is feasible only on small collections or for larger ones for which extensive funding is available.

The approach that we have come to call the “Troup process” allows us to leverage existing file-level description to make a much larger volume of material with fewer resources while still meeting national standards for imaging and description. With the TEI process, a project of 1,000 handwritten pages is a large undertaking that would cost upwards of twenty dollars per page to convert and deliver. For subsequent projects using the Troup process, we are asking funders for approximately one dollar per page and can absorb projects of 50,000 – 100,000 pages.

In digital library work, the largest share of the expense has not been imaging, but rather description and delivery. The Troup process flips the equation, making scanning and image processing the focus, allowing for a larger through-put of images. File-level, Dublin Core metadata is generated in a partially automated fashion based on existing description extracted from the finding aid.

There are tradeoffs. Full-text searching of hand-written material is lost. Item-level description is sacrificed. The Troup process is, however, more in line with the file-level approach generally applied by archivists. Indeed, the highly influential 2005 article “More Product, Less Process” by Greene and Meissner argues that archivists should only in exceptional cases describe records lower than the file/folder level. The gain that the Troup process provides is a more direct correlation between a collection finding aid, the folders described in its container list, and the corresponding file/folder-level digital surrogates. The Troup process preserves the inherent structure of a collection and access to digital surrogates via the finding aid, while also providing highly interoperable Dublin Core metadata records that may be ingested into other database systems. In our case, these records are available via the Digital Library of Georgia portal.

The results of the Troup project serve well the objectives of the NHPRC “Digitizing Historical Records” program and, no doubt, will serve as the basis for many useful projects to come.”

At the Troup County Archives, we are very excited about the success of the records. At this point, we are anxious to hear from researchers who use the collections online. We did work with historians and genealogists at the Archives to get their input to having the records available. They were very positive and helped direct some of the work processes. We do think that scanning without creating new metadata is the only feasible way to make such a large collection of records available. We look forward to being able to use these records for many many years to come and making 19th century court records of Troup County available to researchers and genealogists in the United States and around the world.

Wednesday, September 9, 2009

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)